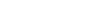

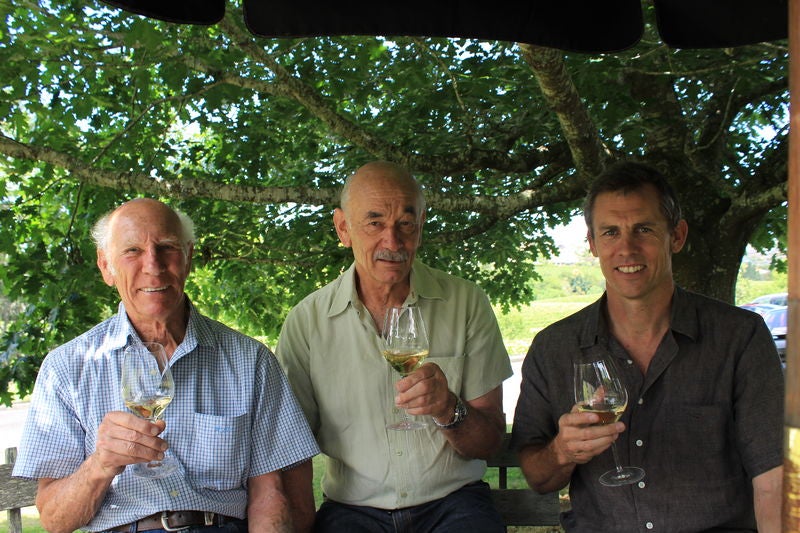

Babich Wines is a family-run winery based predominantly in Marlborough, New Zealand. Its first vines were planted by Croatian migrant Josip Babich in the Henderson Valley, West Auckland, in 1912. The company now has 14 estate-owned vineyards across Hawkes Bay and Marlborough, with Josip’s grandson David Babich at the helm as CEO.

During a trip to London last week, David Babich spoke to Just Drinks about New Zealand’s recent cyclone, vintage ’23, water conservation and why developing export markets is the best way to protect Sauvignon Blanc.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

JD: We’ve all seen the headlines on Cyclone Gabrielle, how has Babich been impacted?

DB: As far as international markets go the cyclone is mainly a Hawke’s Bay issue. We have five vineyards in Hawke’s Bay. I was down there about two weeks ago and it’s like a warzone. It’s quite incredible. You’re driving around, there’s silt everywhere. And then there’ll be an orchard with five or six cars on their roofs that have been washed in and they just haven’t got around to clearing them out.

There’s forestry slash – so that’s all wood that they leave behind – silt and flooding damage. I think the tally was 12 deaths but it had the potential to be so much worse. A lot of people will have near-death stories.

I think they’ve calculated that the wine industry have lost 500ha of grapes. The grape vines at our Fernhill vineyard are not capable of being stood back up. The nets are capturing all sorts of rubbish. There’s silt on it. There were 15 dead sheep in the vineyard.

A few hectares were fine, but we just can’t harvest them. It’s too wet, the rows have fallen over so you can’t put a harvester down and you can’t get a workforce to hand pick it. The wick bins for picking have all floated away. We’ve just written the crop off that whole vineyard.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalData

JD: Will the damage impact your stocks this year?

DB: On that vineyard we had Sauvignon, which we have a lot of in Marlborough, and Chardonnay, which we have in Gimblet Gravels. So we won’t have a product gap, we will get about the right amount that we need, but we won’t be making our premium Chardonnay for the first time this year – we’ve made that wine since 1985. The grapes are there but the quality wasn’t there.

JD: Do you have any idea of the financial implication for Babich?

DB: It will be small. I think there’s a lot of implications for the industry, at an individual level. But we’ve got 14 or 15 vineyards and this is a very small one. The people I think of are those with one vineyard – that would be truly devastating. There’s a lot of vulnerability which is coming to light.

For us, it’s 1.5% of what we do. Notwithstanding, I’ve known that vineyard for 30-plus years and it is just unrecognisable now. It’s on the ground in a really bad way, it’s just a brown moonscape.

JD: So how is the ’23 vintage looking, outside of the damaged vineyards?

DB: For all of the challenging weather, our Hawke’s Bay sites are looking in really good condition. There’s still a long way to go but, as of last week, the Merlot was sort of crunchy, with very little rot.

We run quite good stock in the winery of Hawke’s Bay. We will have a shorter vintage of supply on things like Bordeaux reds and Syrah and even Chardonnay out of Hawke’s Bay. We’ll just run with the ‘21/’22 vintages longer, and launch ‘24 sooner and bridge that. So continuity of supply will be I think unaffected for Babich.

I think generally 2023 is going to be a pretty tough vintage for Hawke’s Bay but it might not have a strong effect on the supply side because wineries do carry stock of previous vintages. I don’t think there’s going to be a huge amount of the ultra-premium coming out.

It’s hard to sit in Auckland with 60 days of constant rain and not project that onto Marlborough. But our viticultural guy is saying: “Step back from the ledge, it’s not that bad!” It’s better than last year – and we did a good job last year so that gives me some perspective.

In terms of size, I think we started off thinking it was Marlborough’s regional long-term average plus 10-15%. Now I’m edging more towards long-term average, which is about 12.5 tonnes per hectare per year. I think what we would like to happen is we get an average vintage. We had a big vintage last year, so don’t want to freak the market out with two big vintages. The worst would be a very small vintage like ‘21 – that’s just damaging, it’s really hard to navigate that.

JD: What are the biggest cost pressures Babich is facing?

DB: In the last five years, the cost of Sauvignon has gone up from NZD1,700 (US$1,055) to around NZD2,300 a tonne. So, in a carton of wine, the most significant cost would be cost of grapes. In the last 18 months, it would be wage growth and energy costs.

A tonne of grapes will probably still go up but maybe not at the same as before. That’s one of the reasons why we want things to be a bit more static. If a small vintage bounces the price of grapes up, that would then result in a cost increase that has to be passed on and then we are contributing to inflationary pressures. Whereas with energy and wages, if we can have a solid vintage, then I think we can just absorb those costs with scale growth.

JD: Have you been experiencing labour shortages?

DB: There are two things in particular that we have been dealing with, one being New Zealand’s zero-Covid locked-borders policy. Our vintages are typified by 20 to 25 people coming in from overseas who do three vintages a year. We were pulling in whatever backpacker was floating through the region for the ’22 vintage. It was the least-experienced crew we’ve ever had. You’ve got a real challenge of showing people what to do and ensuring they stay safe in the role.

Now the only impediment is the cost of plane tickets. It’s going take another two or three years until that settles down.

The labour shortage we’re seeing now is more through other parts of the organisation. We are struggling with viticultural workers. We get a lot of people coming most recently from South Africa, as they’re sick of having no electricity and blackouts [due to domestic ‘load shedding’]. They’re great people to have on board as they’re coming from wine farms – and they know what safe operating looks like.

We can generally find people to work in the winery, although we have noticed it’s tighter than it has been. But, on the general running of the business, logistics, administration and finance roles, it’s harder to get the right person and you’re paying them around NZD10,000 more than three years ago.

JD: Why are your efforts on sustainability an area of focus for the business?

DB: We’ve been running this winery for 107 years and I think when you’ve done it across generations you understand that you’ve got to keep the wheel turning. At the heart of sustainability is: can the next generation do it with the ease with which we are?

That’s my family’s macro view. And my view is that that shouldn’t be harder than what my grandfather faced because he was into sustainable farming. The simple question is: am I taking out more than I’m putting back in?

You have to be a bit focused in this area. You’re mindful of everything but you pick your battles. We focus a lot on water conservation. We just spent NZD50,000 pulling stones out of a river on one of our vineyards to ensure it continues to flow well in the summer months. It’s a constant investment keeping watercourses operating well.

We actively measure our conservation of water within the winery. Our most recent number is something like 2.1 litres per litre of wine produced and that used to be three or four litres. It’s about taking an interest – we talk about it a lot in the winery. It’s really easy if people have the right mindset.

The other thing that we can really use is dams and securing water when there’s lots of it, which is winter. We have the Southern Alps which melt in Spring. Dams are a million dollars a pop and so they are expensive capital assets, so you tend to have a five-year view on them. We’ve put in two dams just in the last few years to fill in a couple of vineyards.

JD: What’s the biggest sustainability issue facing the industry?

DB: I’d say climate change, because we were just getting a greater degree of weirdness. Weather is hitting us in volumes that is just hard to manage. Now if I’m buying vineyards I actively avoid ones with watercourses because some little stream can turn into a raging out-of-control torrent when some atmospheric river does its thing above us. And they’re too damaging. So it’s the extremes of climate change that we’re dealing with.

That would be the very big picture but the subset of it is water management. ‘Too much’ or ‘not enough’ are the two settings that we are increasingly having. Storing water is the way to go because Marlborough can go two years without rainfall. When you go two years without rain, dryness in the soil substrate can go down three metres. You get 100-year-old gum trees die because of drought.

JD: All your vineyards are sustainably certified. How important do you think regulation is? Is it necessary in order to keep businesses accountable?

DB: I really think it is. I think sustainability needs framework and audit profile. There’s no point in having something you’re not auditing. The New Zealand Winegrowers sustainability programme is really well run. It’s quite independent and the criteria keeps advancing. So it’s not a static thing but the framework is well understood and communicated. It’s resourced well. We have annual sustainability audits across our vineyards and winery.

JD: One of your targets is to double your sales of organic wines from 2018 to 2025. Is that demand-driven, or coming from a sustainability perspective?

DB: It’s a bit of both. We have to make the first steps to convert vineyards to organic in order to have the supply. So it’s definitely supply-driven. If we want to grow, we must make the first step and create the additional vineyard area.

Then we have to go out to the market and convince the market or meet demand, and there is a bit of both. Wine buyers are happy to see something different, and organic definitely fits differently, but the wine must be really good.

Something I saw in the US five to ten years ago was a blurring of organic, natural and orange wine and that’s not a good experience for the consumer. Consumers sort of lumped the three things together, and then didn’t think they liked organic wines. What we’ve been really focused on is making extremely good single- or dual-vineyard organic wines that are exactly what people expect. These are premium wines, so they come with a bit of a reserve price, but we’re really mindful of the pricing.

Consumer feedback shows they would be open to organic if it was the same price. That’s the caveat

The fact is, organic grapes cost more to grow. We’re trying to resolve that but we haven’t figured it out yet. Every discussion about organic is how can we get this yield looking more like conventional? There’s a double hit on it. It costs us more to run the vineyard per hectare because the weed management side is so much more challenging but, because of the amount of weeds and other competition in the vineyard, you get a lower yield as well. The cost of producing the wine itself is identical but the input costs are higher for less.

Consumer feedback shows they would be open to organic if it was the same price. And that’s the caveat. We are working quite hard to close this gap. For example, we’re trying to grow things that will naturally die off, like a clover cover crop. We’ve tried weed mats but then when you get 60-mile-an-hour winds there are weed mats everywhere. It’s trial and error!

The wine industry is about innovation. You’re always trying to innovate and keep your eyes open about what’s around the corner. We’re trialing stuff in the vineyard and the winery all the time.

JD: How do you think the New Zealand wine industry will innovate looking forward, following the success of Sauvignon Blanc?

DB: I think – well, because I want it to! – that Sauvignon will continue in its popularity in the markets we currently sell in. We’re seeing a lot of uptake in Asia as well and that represents a new market. But the main export markets are still Canada, the US, UK, EU and Australia.

There’s always going to be a commercial proposition around Sauvignon Blanc. That’s the heartland of what’s happening: daily, accessibly priced Sauvignon which ticks all the boxes.

But I think you’ll also see a dial-up, even at the commercial level, of sustainability. And then, as you push into the more innovative space, you will see a degree of premiumisation, which can be single-vineyard expressions, sub-regional expressions, for when consumers want a step up from their normal drink. They’re two to five quid more but all of that money goes on quality – you get twice the wine for a few quid more.

JD: Do you think New Zealand could, at some stage, suffer from having all its eggs in one basket in the eyes of the global consumer?

DB: We are all in on Sauvignon. We are fully invested as an industry. Cabernet is not going to save us. I have this discussion at home, you know, we’ve put our bets down here.

If you want to mitigate the risk profile of the UK saying: ‘Anything but Sauvignon,’ don’t mitigate it by making Pinot Gris per se. Because the demand is not there. Develop Asia. Go to India and set up in Mumbai trading. It’s about market development, not product development. This is where the answer resides. Risk mitigation has got a very good market answer, not getting away from where you put your bet and saying: ‘I’m going to grow Bordeaux reds.’ That’s not the white knight for us.

At the moment we sell 85% of our wine to 15% of customers in traditional markets in Europe, Australia and North America. Asia is what we need to develop, so if someone says ‘Anything but Sauvignon’ over here we can go sell it in South Korea.

What our government needs to do to assist us and get a free trade agreement with India, for example. We have an FTA with China which has been great. That’s been in place since 2008. China is in our top five or six markets. Asia is easy for us to export to as well.

Our strategy is we’re always happy to sell Sauvignon, and we will show you six different Sauvignons which all have a reason for being.

JD: Can you talk a bit more about the Asia market? China in particular is more known for importing bigger reds than Sauvignons?

DB: We’ve got a team and a warehouse in China – so it is significant. And we see Asia in general as a future market. Collectively Asia is quite big for us.

We’ve seen a transition in China. We’ve been there a long time – 20 years on the mainland and 30 in Hong Kong. Our typical sale ten years ago was a container with 90% Bordeaux-style reds and then 10% other things. Now it’ll be a container of Sauvignon. They have figured out that if they want Bordeaux red, buy it from Bordeaux or South America. But what New Zealand does is white wines and they are learning this. The influencers get educated because they go to university in Australia or New Zealand, come home and go: ‘This is what we were drinking.’

There are an estimated 40m dedicated wine drinkers in China, drinking wine as a preferred beverage two or more times per week. The entire population of Australia is around 26m, so probably has 10m dedicated wine drinkers. So you see the capability of the China market. You have just got to be able to access it and activate it.

JD: What’s the most exciting market in Asia?

DB: China is exciting because of scale. It’s a big place and the eastern seaboard is definitely getting tuned in. You can have a big customer come out of nowhere. The US can be like that too. You get a grocery chain you’ve never heard of that has 4,000 outlets.

India is the other one that’s hyper-interesting but very hard to activate, mainly because of tariffs. We’ve got to get to an FTA with India. China wasn’t activated until we had an FTA, so there’s a political level.

We’ve been in India for quite some time, just keeping things simmering. We don’t have any big push there because the wine is just too expensive but, if the tariff regime comes off over a three-to-five-year period, you’re in business and we’ll push hard. There’s definitely a really strong wine culture in India.

Some other markets just outperform. Like the Maldives. It’s very small, but we have an extremely good distributor there. They’re certainly disrupted at the moment because of travel bans with Covid, and they usually have a lot of Russian [tourists]. But you get these little markets that are like bolters, and they just way outperform what your expectations are. It usually comes down to a really dialled-in distributor.

How New Zealand winemakers are innovating in a Sauvignon-dominated industry